Whitepaper: How a Truly Islamic Financial System Would Work

Ibrahim Khan

Co-founder

54 min read

Last updated on:

Why write this piece in the first place?

We want to sort out money and finances for Muslims once and for all.

We are tired of the endless debates at dinner tables on Islamic finance and if it is truly Islamic. We are deeply concerned by the sense of compromise felt by those who do end up using Islamic finance as well as the guilt felt by those who don’t.

The way to resolve this issue once and for all is to fix Islamic finance. We can’t do this alone, and are self-aware enough to know we don’t have all the answers. But this whitepaper is a start.

The issues with the modern Islamic finance system arise primarily out of the following:

- The entire financial edifice they operate within is unislamic – and so any products the Islamic finance industry do come up with are blighted by inadequacies. (the “Edifice” issue)

- The Islamic finance industry has never really faced serious pushback from the constituency that matters most to them – their customers. (the “No Pushback” issue)

- There is a received wisdom within the Islamic finance industry that a “truly” Islamic product is just a mirage and the best way to structure an Islamic product is to start with a conventional product, and look to “Islamify” it. (the “Conventional First” issue

To solve (1) we need to propose a genuine alternative financial edifice and we will need strong support from Muslim-majority countries and their central banks.

To solve (2) we need to mobilise Muslims and educate them on what they need to kick up a fuss about.

And to solve (3) we need to show that genuine alternative products are possible and encourage a new way of thinking within the Islamic finance industry by using (2).

Solving the Edifice issue is at the heart of the entire solution. Absent a solution to this, any product coming out of Islamic finance will likely be a compromise. Also, absent a viable alternative to the current financial system, any criticism of modern Islamic finance will be (correctly) met with a “right, so you come up with something then.”

This is the divine pursuit too. In Surah Furqan the disbelievers expressed their surprise at a messenger that “walks in the markets”:

“And they say, “What is this messenger that eats food and walks in the markets? Why was there not sent down to him an angel so he would be with him a warner?”

In the minds of these disbelievers the sacred is not to be linked with something as base as our appetites and commerce. But this thought process is faulty.

God is not a curiosity; a pastime to make us feel warm and fuzzy inside on an evening in our leisure time. Rather, he’s the north star that we seek at even as we eat and transact. Doing “God” is an all-encompassing pursuit. Islam is the colour of the spectacles through which we see all of life – it is not the resplendent garb we put on for a wedding.

The summary of our core proposal is: modern finance is an important industry that should do a few simple jobs for us in the economy. Modern finance has vastly overreached its remit and is dangerously broken. we believe a truly Islamic financial system is practically possible today. Such a system solves the knottiest issues around injustice and stagnant growth facing modern finance.

This system will:

- be built upon a fairer way to create money; and

- materially change incentive structures and promote more productive economic activity.

To get there we need to:

a. show robust proofs of concept;

b. kick up a fuss with central banks and government; and

c. proactively present Islamic finance as a solution to global problems rather than a niche adaptation of conventional finance.

Now, when Islamic finance practitioners go about their work with a renewed vigour in their stem and the end clearly in mind, they do so with greater purpose and work on things that are pointed and focused rather than directionless. Collectively we will have dealt with the Edifice, No Pushback and Conventional First issues.

In this whitepaper we will:

- Outline the issues with the modern financial system and argue that a new financial system is possible – and sketch it out;

- Outline the issues with modern Islamic finance industry and sketch out alternative “truly”[1] Islamic financial products;

- Set out a viable roadmap to go from where we are today to a “truly” Islamic finance industry

- Set out a viable roadmap to getting an Islamic financial system adopted across an entire economy and, ultimately, the global economy.

A quick note: we primarily use “finance” to mean debt finance in this essay. Islamic equity finance does not face most of the issues associated with Islamic debt finance.

A quick caveat: this is a working document and we will adjust and tweak it over time. This is not intended as a definitive piece on this subject; rather it is intended as a way to organise our own thoughts and to stimulate further work by us and others.

What is the nature of this solution and where is it going to come from?

Discussions within the Muslim community around finance and Islamic finance centre around three broad camps:

- Conservative: This group broadly argue that the sharia rules around money are to be applied broadly to capture most things and are to be interpreted in a strict way. This usually results in the conclusion that most conventional finance products are not permissible and most Islamic finance products are unsatisfactory. Usually, proponents of this view will end up sitting on the side lines of finance waiting for something truly Islamic to come along.

a. There is a subset of this group who hold the same fiqhi views, but actually veer off in the complete opposite direction and conclude that, as finance is a day-to-day need, and as Islamic finance is “just the same as conventional finance but more expensive”, one can just go ahead and use conventional finance.

- Practitioners: This group are typically in the Islamic finance industry. They are usually entrepreneurs or bankers. They are driven by two motives usually – desire to deliver something to the Muslim community that meets needs and desire to make profit. Their approach is characterised by a degree of pragmatism, commerciality, and “the path of least resistance”.

- Permissive: This group broadly argue that sharia rules should be interpreted narrowly when it comes to finance and effectively do not capture most of modern finance. They conclude that it is permissible to use modern finance and that there is no need for Islamic finance.

This is not the essay to be digging into the Permissive approach. Suffice to say that we hold two statements to be obviously true:

- The sharia has a lot to say about financial matters and the conduct of transactions

- The modern financial system is broken

If those two statements are true, then we’re going to have to reimagine our financial system anyway, and it would be very odd for a practising Muslim to not base our reimagining work on the sharia financial teachings. It is not acceptable to just shrug our shoulders and carry on using the current financial system.

We can’t read a verse like this and but stop in our tracks and really think about what it means for our world today:

“And whatever you give for interest to increase within the wealth of people will not increase with Allah. But what you give in Zakat, desiring the countenance of Allah – those are the multipliers.” (30:39)

And

“O you who believe, fear Allah and give up what remains of your demand for riba if you are indeed believers. If you do it not, take notice of war from Allah and His Messenger.”(2:278-279)

The Conservative group, on the other hand, agree there is a problem. Putting it crudely, some of them respond by saying “it’s all haram, just carry on renting your entire life”, while others respond with “if you can’t beat them, join them (under necessity)”.

The reason both Conservative approaches fail is because they’re defeatist by nature. They are opining on modern Islamic finance in isolation whilst shrugging their shoulders at the global Edifice problem. But that’s not a solution-oriented approach – that’s being a critic without anything viable to propose as an alternative. The long-term solution cannot be “carry on renting” or “let’s just use conventional finance”.

Our parents did not come to this country without any Masajid and halal meat and just shrug their shoulders and say “ah well, let’s just be vegetarians and pray at home”. We can’t do that either with our generation’s problem.

The Practitioners are actually doing something – which is commendable. However, there is a healthy dose of mercenaryism running through this group, and many in this group are not Muslim. That alone is not a reason to write someone’s contributions off, but it is fair to say that a non-Muslim is unlikely to have ambitions to pave the way to a global financial system underpinned by Islamic teachings as an end. The Practitioners are simply there to a solve a problem and make some money whilst doing it.

We believe that a solution needs to come by breaking out of these three paradigms. Muslims need to come up with a roadmap, situate ourselves on that roadmap, and then drive ourselves in the direction of a better future. The solution is not a point of view, it is a mindset of dynamicity, movement, and progress. The solution is the conviction that we’re not settling for anything less than the ideal, and we have a clear path to get there.

We need the Practitioner to embrace the mindset, and come up with new Islamic finance products that get us down our roadmap quickly. We need Conservatives to educate their community with a critique of what currently is, but now also a realistic sketch of what could be. We will need the Permissive group to get inspired by a better, Islamic way of doing finance rather than settling for the broken conventional financial system.

The important of situating ourselves on a roadmap and stating an end goal that is appetising cannot be understated. Without doing that, Islamic finance today will always look unsatisfactory. But, when understood as an interim stage on a compelling roadmap, modern Islamic finance suddenly has the chance to be inspiring.

Proposing a vision and redirecting critical energies of Conservative and Permissive groups on the development and critique of this desired goal is far more productive than a defeatist critique of the modern day.

Proposing a vision and striving towards it is also a Prophetic and Islamic methodology.

Remember Our servants Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, all men of strength and vision.(38:45)

Yusuf asked to be put in charge because he had a gameplan:

Joseph said, ‘Put me in charge of the nation’s storehouses: I shall manage them prudently and carefully.’ (12:55)

Similarly, Sulaiman asked for incredible power because he had a gameplan:

He turned to Us and prayed: ‘Lord forgive me! Grant me such power as no one after me will have- You are the Most Generous Provider.’ (38:35)

Similarly, the wife Imran (the mother of Mary) had pledged what was in her womb for God, expecting a male. But when she got a girl, she was really surprised (perhaps dismayed?). However she still stuck to her plan and followed through. Jesus (as) was the result.

We should now be clear on what the nature of the solution we need is, the importance of fighting for such a solution, and where it is going to come from.

How does the modern financial system work?

Let’s first sketch out how the modern financial system works – and then we’ll turn to what’s wrong with it from a sharia lens and how to fix it.

Today the financial system has become a huge part of our global economy – around 24% of global GDP is attributable to the financial sector[2].

But it wasn’t always that way. The financial sector has gone on a crazy, artificial, growth trajectory.

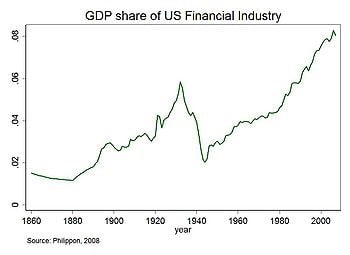

[3]

[3]

The graph above shows how we have been deregulating aggressively since the late 1970s – particularly in the USA and UK – and that has led to a massive expansion of the financial sector from little over 3% of the total GDP to over 8% today.

If you add in insurance, real estate, and professional services – highly interconnected industries to finance – the total GDP share jumps to a remarkable 34%[4].

In the UK, the story was similar, with the financial sector expanding to about 8.3% of the total GDP today, and if you add in professional services, over 12%.

This sounds very fishy, but perhaps, you might say, the financial sector just grew. Sure, it’s large but it’s not at crazy proportions.

The issue is the financial sector is not like any other sector. They are the sector entrusted to hold the money of the entire economy and so any turbulence or risk-taking materially affects us all.

And things materially changed in this period. The riskiest part of the financial sector – investment banks – quietly traded pieces of paper among themselves with increasingly inflated prices.

To give context, investment banks held $33 billion in assets in 1978 (1.3% of the GDP), but by 2007 that had expanded out to $3.1 trillion (22% of GDP). Specifically, the instruments that caused the global financial crisis of 2007/2008, collateralised debt obligations (CDOs) constituted $4.5 trillion in assets in 2007 – 32% of the US GDP[5].

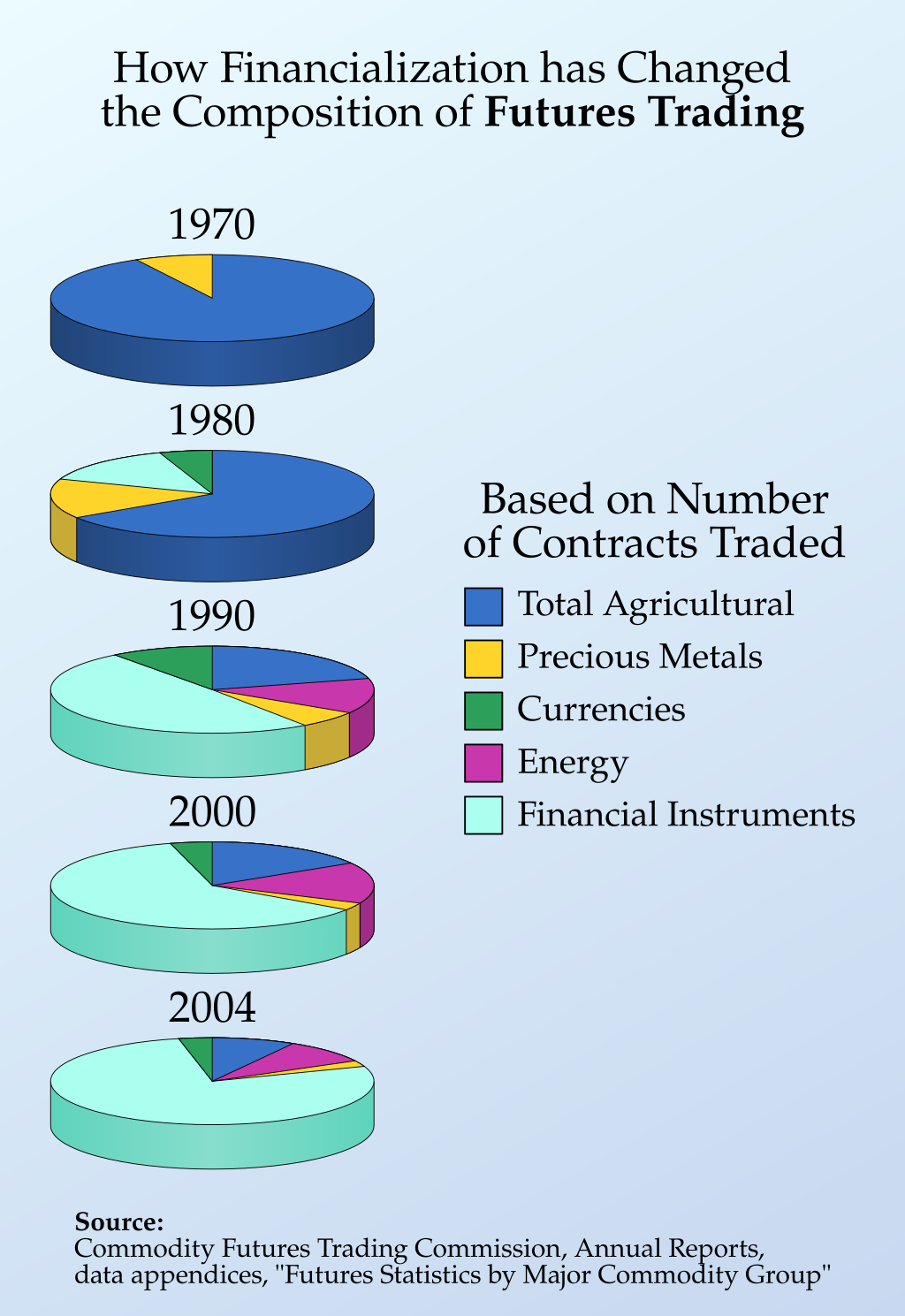

Another way to see how far these weapons of mass destruction – as Warren Buffett allegedly referred to them as – had expanded is by looking at the futures market. Futures are the bulk of derivatives transactions and they were originally used for practical, useful things for specific industries that needed to smooth over prices and build in certainty.

However, over the decades the entire industry has been subsumed by futures based on financial instruments used for trading between bankers in the City:

[6]

[6]

Yes, the whole thing is slightly absurd. The value of the assets underlying derivative contracts is three times the value of all the physical assets in the world[7].

In the UK the picture is the same. John Kay eloquently explains this.

The assets of British banks are five times the liabilities of the British government. But the assets of these banks mostly consist of claims on other banks. Their liabilities are mainly obligations to other financial institutions. Lending to firms and individuals engaged in the production of goods and services – which most people would imagine was the principal business of a bank – amounts to about 3 per cent of that total. [8]

Financialisation has also caused a major increase in the volume of debt in the USA too. From 1973 to 2005, total debt rose from 140% to 328.6% of GDP. Over this time the financial sector debt grew particularly fast – from 9.7% of total debt to 31.5%[9].

Clearly something is amiss. But the financial system wasn’t always like this. At heart the financial sector has 4 important jobs to do – and we need it to do those well for the whole economy to function like clockwork. Let’s sketch those out.

Breaking down the jobs the financial system does for us

Payments

The first, and probably most important job the financial sector does for us is provide the rails and infrastructure for us to be able to make payments to one another. This is a surprisingly complicated affair, involving multiple parties playing different functions using different technologies.

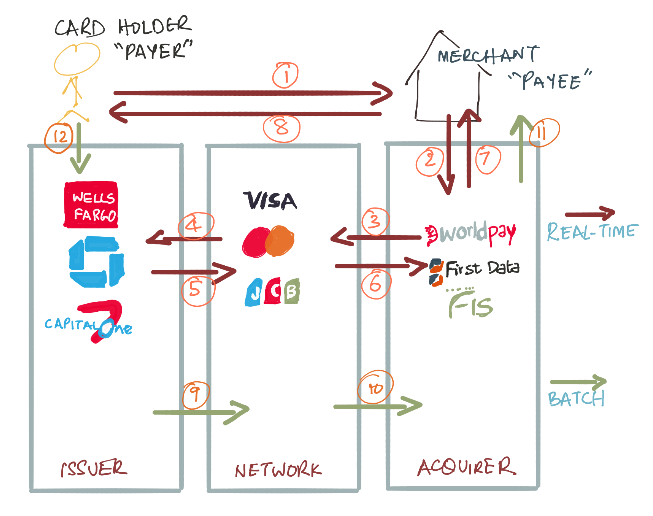

This article is a great summary of how it all works, and summarises it nicely into this diagram:

There are multiple modes of making a payment and getting it from one person/entity to another. Layer in cross-border transactions, regulation, and different infrastructure in different countries, and this actually starts becoming a very complex problem.

Banks and financial institutions can and do solve that for us today – although anyone who has recently tried to undertake a financial transaction involving a bank will attest that the system is still a way off perfect. The cynic would suggest that, perhaps, if more bright minds were focused on this rather than trading pieces of paper with each other, we might have progressed further.

Financing/Investment

The second key role the bank plays is connecting up those with money and want to park it somewhere to those who need it to do productive things with.

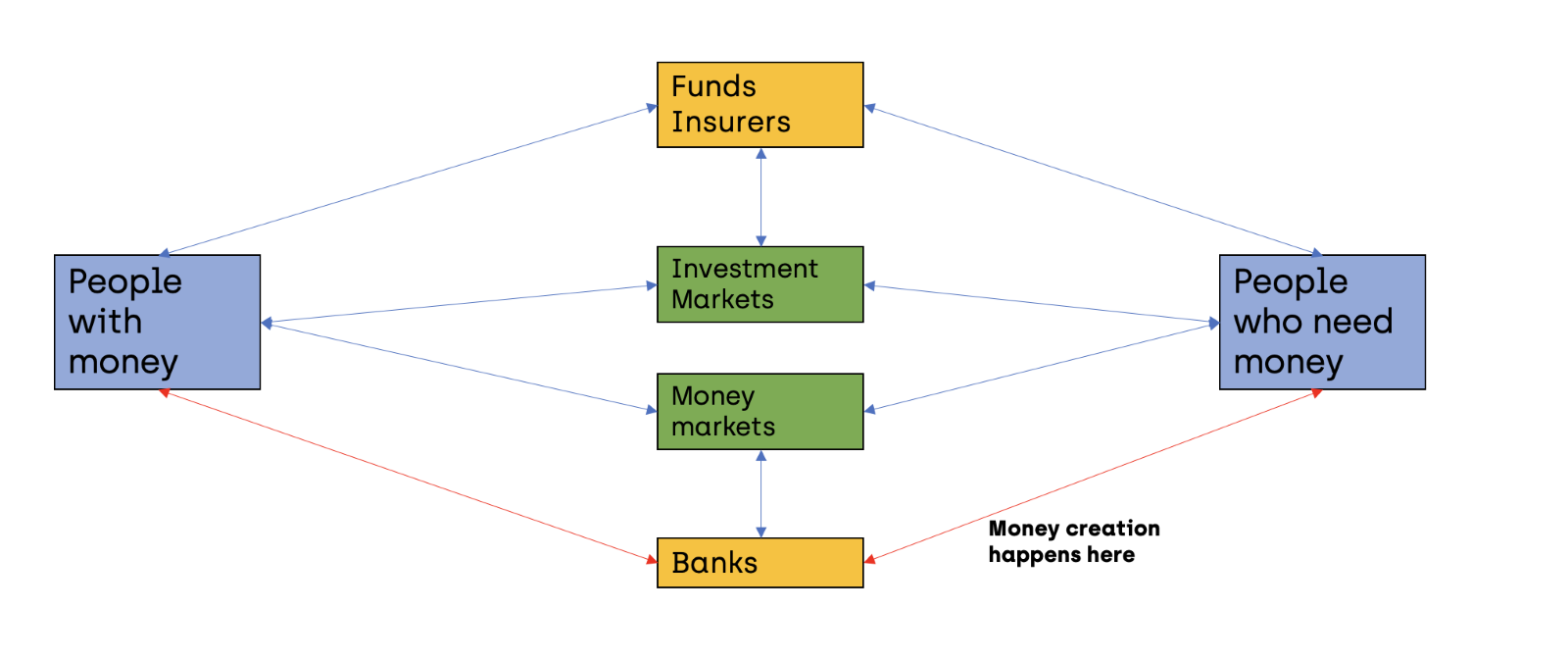

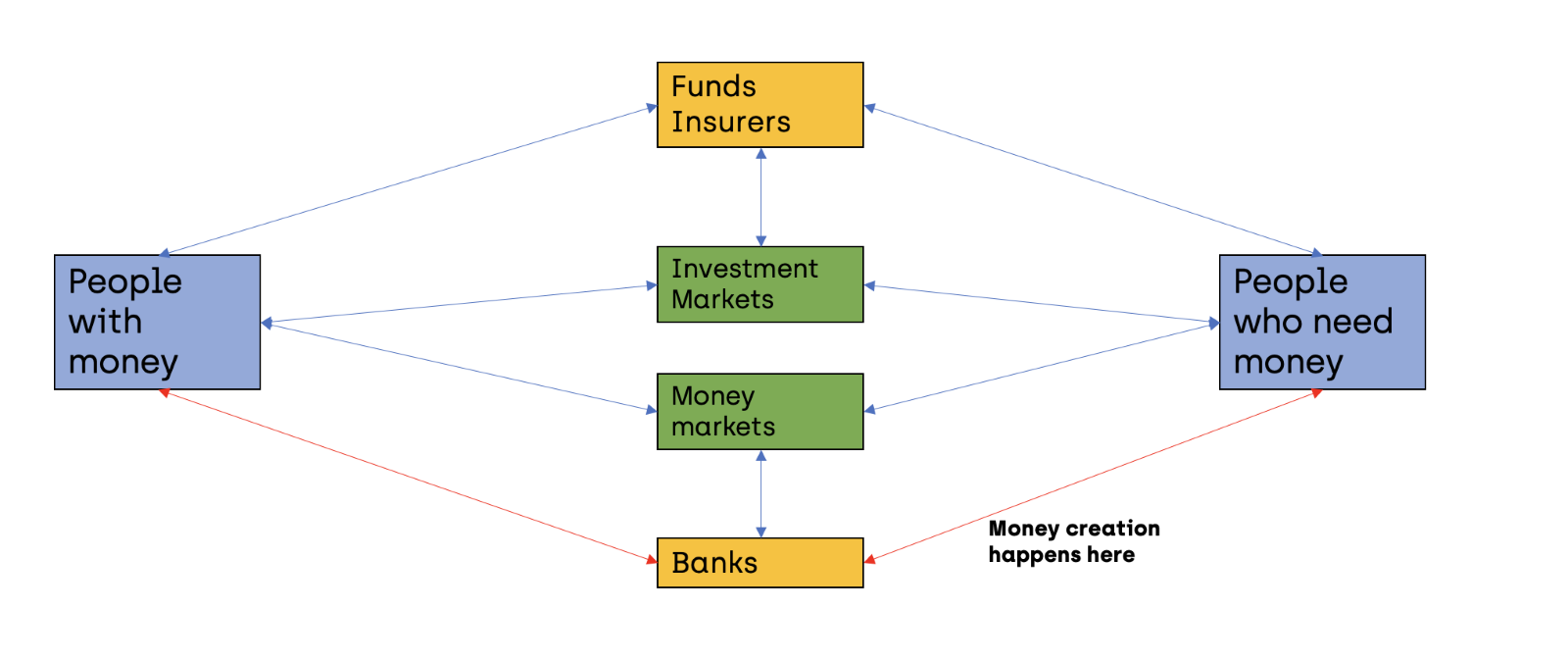

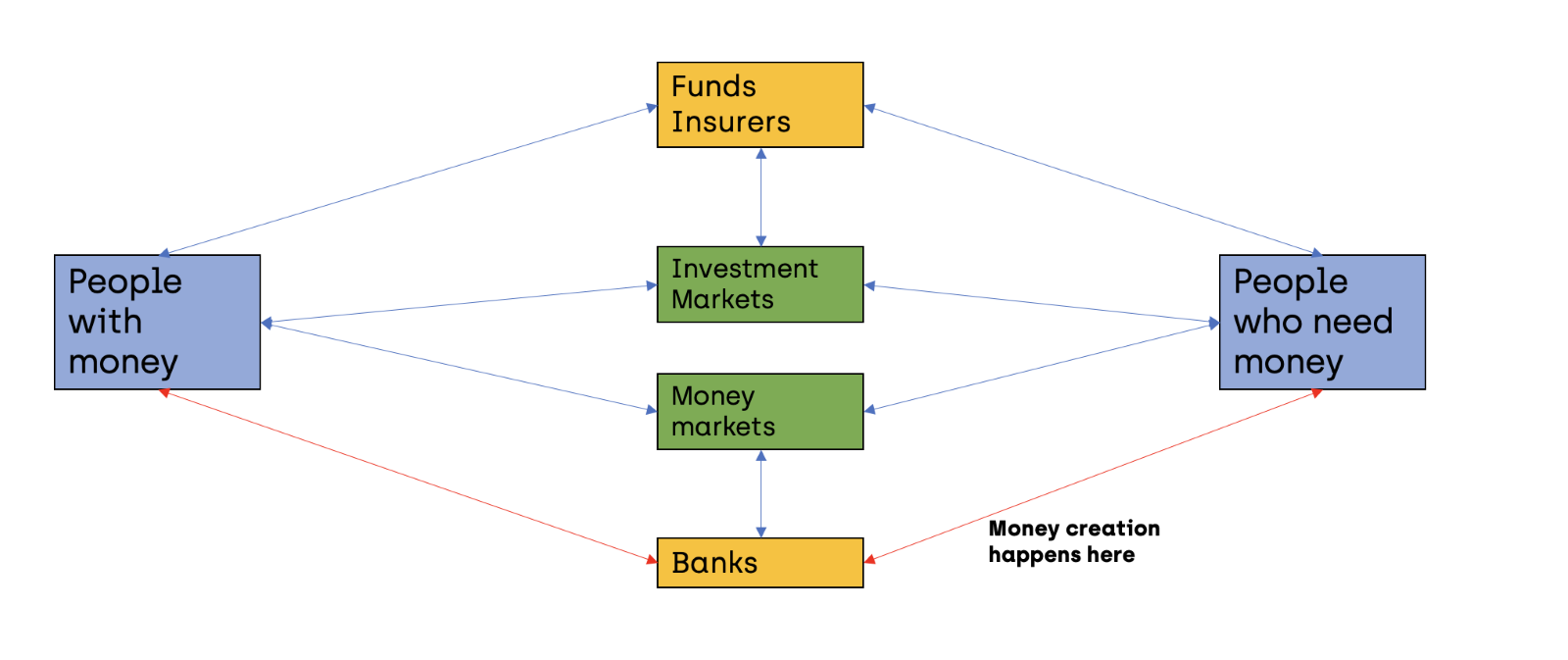

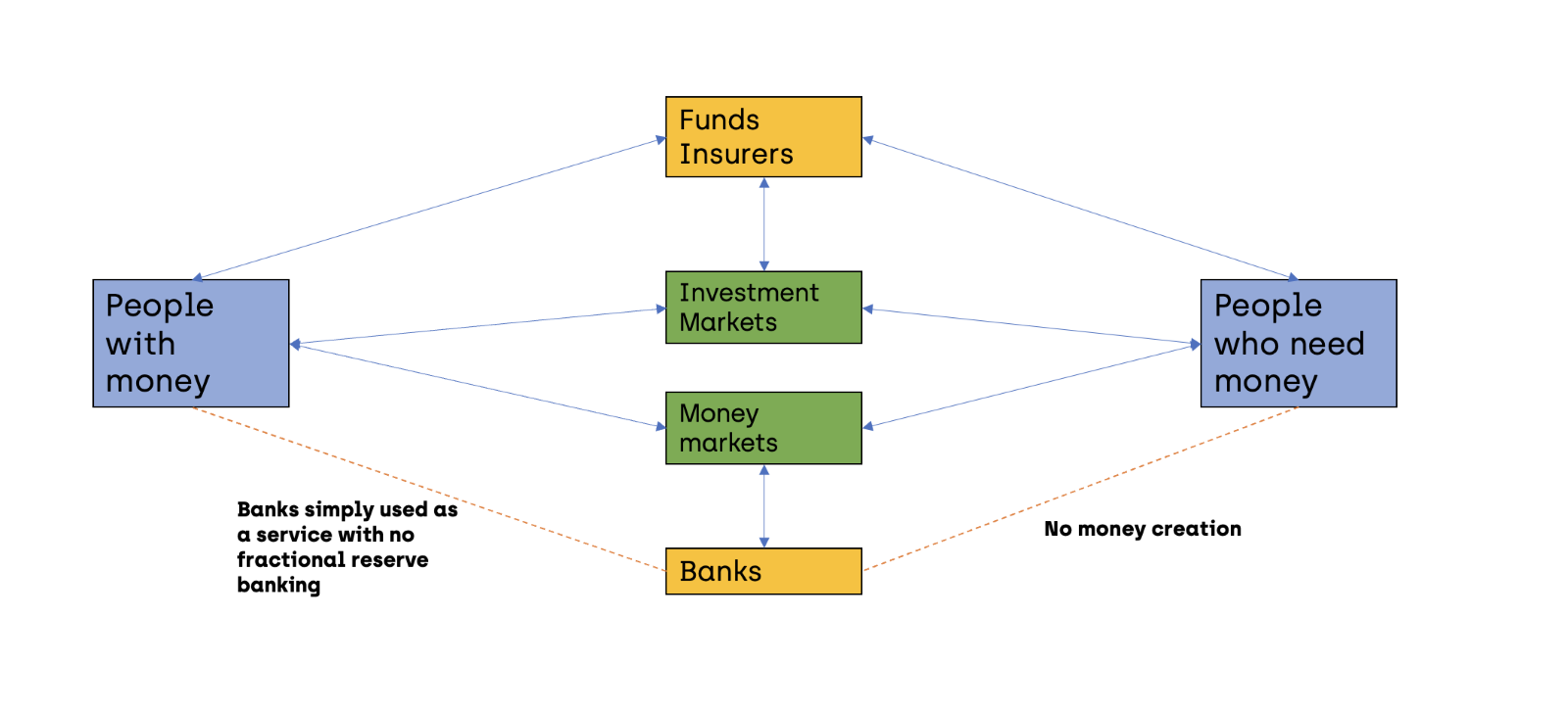

The below diagram summarises the flows:

People with money (on the left side) have two potential intermediaries whom they trust with their money and whom ultimately will deploy that money into various investments/loans (to the “people who need money” on the right).

The first route is funds and insurers who “invest” the money into various endeavours. The second route is to deposit the money at banks, who will then lend it to others.

The crucial difference between the two routes is that the banking route is almost entirely debt-based, while the funds route is usually equity-based. Additionally, banks can create money due to the regulatory powers they are given to operate fractional reserve banks (don’t worry, we will explain these concepts shortly), while the funds/insurers cannot do this. If funds/insurers are given £100, they invest £100, while if a bank is given just £8.50, it can loan out £100.

Insurance

We featured insurance companies in the above diagram, and model it in the same bucket as a fund. This is not strictly true.

When we buy insurance, we are selling the risk we are exposed to, and the insurance company is buying it. This money is then sat with the insurance company and it is up to them to ensure that they have enough money to meet claims as they arise, whilst at the same time make certain investments with the money in order to make some profit.

There are certain catastrophic outcomes that are highly unlikely (but do happen) for which insurance is perfectly suited, and it helps us in our lives if we have a function that allows us to accommodate for those instances where we have a car crash or a house fire.

We have previously written our views on mainstream insurance here, but even if you consider insurance to be generally impermissible, you will be fine with takaful insurance (a variant of cooperative insurance). The point here is not to get into the debate of how to deliver an insurance financial product, more that there is a need for such a product, and it plays a function in our modern economy.

Clearing & Exchange

Finally, the financial system is a great lubricant of trade and a venue for transactions to take place. If we revisit the below diagram again, we can see the central role “markets” play in the entire system:

The intermediaries (funds, insurers, banks etc) who hold financial instruments (debt or shares) often need to sell them to others to release capital. This is where the investment markets (also known as the stock exchange) comes in. For debts, there are the money markets.

Currencies are also exchanged at an enormous level daily and there is a separate interbank market that facilitates these transactions.

This central market system is vital to the seamless functioning of the financial system. If there is no central market, then counterparties need to find each other, do due diligence on each other, and come up with a deal that works for both. This makes each deal highly costly and time-consuming.

Now, a central market allows transactions to be handled in a much quicker, more reliable and seamless way – often allowing transacting parties to avoid counterparty risk too (the exchange will say “we’ll honour things if the other party defaults” or “we are holding both the asset and the money in escrow and will facilitate this deal for you”.)

Issues with the conventional financial system

So far we have trailered that something is clearly very broken in our modern financial system, it has ballooned beyond all comprehension and control, and leads to materially harmful economic cycles in our economies for which ordinary folk end up picking up the tab.

We have also sketched out the primary purposes of a financial system – these functions are useful and should continue to be performed.

So how did we end up from blamelessly providing just the primary functions of a financial system to the mess we are in today? The answer lies with three phenomena that underpin modern finance.

1. The Privatisation of Money Creation

Up to 97% of our money today is not created by the central banks or governments – it is created by private banks. Organisations like Positive Money have done excellent work in detailing this exact point and you can also read about the mechanics of how money is created straight from (one of) the horses’ mouths – the European Central bank.

We have explained how banks create money in videos like this, but in brief this is how the story goes:

- I lend the bank £100 of notes

- The bank now creates £100 of deposit liabilities that it owes to me. I can see these in my account with the bank.

- The bank can then use that £100 to give out – not just that £100 – but more than that £100. Here’s how it works:

a. Initially, many countries have rules in place around how much of that £100 a bank can lend out. Let’s say this is 90% – so £90.

b. However, that £90 ultimately ends up back in someone else’s bank account and now the banking system can issue a further £18 on that too (20% of £90). And the effect continues.

A few clarifying points are important:

- This is a simplified analysis. Technically banks don’t directly take my money and lend that out. The activity of lending out money is separate to the activity of deposit-taking and paying out on those deposits. There is a loose connection between the two in that banks need to maintain reserve cash balances and the proportion of money they can therefore use as loans is indirectly affected by what is happening on the deposit-taking side.

- What enables step (3) above is that bank money (or electronic money) is widely accepted today as money by everyone. Dogecoin isn’t, and neither is bread, but electronic money is. What is electronic money? Money that banks have created in your account with them when they issue a loan to you. Think of it like when American Express reward you for spending through them with additional airmiles. There is no hidden reserve of airmiles that have been deposited with American Express to dish out, they can dish out as many as is appropriate given their ongoing and evolving (a) marketing budget; and (b) relationship with large airlines.

- Let’s put (3) another way – imagine instead of a bank you just loaned me money instead. Now, in order for me to lend that money out, I need to do it using only the £100 – unlike a bank. Why? Because when you send me that £100 – you are using electronic money. You’ll have sent it via your bank to my bank.

- In order for me to be able to create more money than I receive, I need to create my own money. Crypto tokens (or loyalty schemes like Amex, Tesco etc) are an example of this. Instead of lending out that £100, I change that £100 to 100 Ibrahim tokens and agree with you to return my loan in Ibrahim tokens. In your account with me you can see 100 Ibrahim tokens. Now I have a liability in a currency I control the issuance of. I owe you 100 Ibrahim tokens and I also do the same with 100 other people and so I owe them a number of Ibrahim tokens too. While I am waiting for everyone to redeem their Ibrahim tokens in their accounts, I can issue loans of Ibrahim tokens and start earning some interest on them. All this is only possible because my currency – Ibrahim tokens – is accepted as money by others – and, crucially, the Ibrahim tokens I give out as loans – ultimately still end up back on my balance sheet as an account with the debtor.

Banks’ ability to create money was and continues to be restricted by government laws and regulations, however these have been systematically eroded over the years. PositiveMoney captures this nicely for the UK (the story is similar for the USA):

In 1866 there was a banking crisis, and the Bank of England then took on the role of ‘lender of last resort’, committing to lend to banks if they ran out of money to make their payments. Once this safety net was in place, banks reduced their liquid reserves to around 30%. In 1947, when the Bank of England was nationalised, they imposed a formal liquidity reserve ratio of 32%. This reserve ratio required banks to hold £32 of cash, central bank reserves and government bonds for every £100 balance in customers’ accounts. Of course, because government bonds would earn the bank some interest, unlike reserves and cash, the banks would try to hold as much of this 32% as possible in the form of bonds. In 1963 this liquidity ratio was dropped to 28%. Then, in the words of the Bank of England, “Before 1971, the clearing banks had been required to hold liquid assets equivalent to 28% of deposits. From 1971, this was relaxed and extended, requiring all banks to hold reserve assets equivalent to 12.5% of eligible liabilities…. This combination of regulatory and economic factors coincided with one of the most rapid periods of credit growth in the 20th century (Chart 10). It also contributed to an ongoing decline in banks’ liquidity holdings, ultimately to below 5% of total assets by the end of the 1970’s.” In this phrase, ‘credit growth’ really means a massive expansion in the amount of bank-created money, and consequently a massive rise in debt. Finally, in 1981, the liquidity reserve ratios were abolished all together.

Today banks can issue electronic money at scale, and, as governments (1) provide guarantees on bank deposits and (2) have consistently looked to bail out failing banks, banks are the go-to place to park your money safely.

The upshot of (a) our money creation being in the hands of private banks, (2) for that means of money creation to be interest-bearing debt issuance, and (3) these banks being government-guaranteed, results in an economy that deploys capital in the wrong places, increases the debt burden with every passing year, deepens inequality, and increases the potential of a boom/bust cycle and bank crises/collapses.

2. Interest-based financing

Let me preface this section by saying that this is the “problem” with the conventional financial system that we have the least clarity on today. Part of that stems from not having as clear a solution to it as I would propose for the other three problems. Another part of it is that I do not consider that I have spent enough time with the classical sources properly understanding the nature and definition of “riba”.

And part of that also stems from difficulty in being able to calculate implications so far into the future: We know interest is haram, and that a society with it cannot be conducive for the flourishing of the human condition. However, we also know that modern banking has been a significant driving force behind much of the modern growth we have seen starting from the industrial revolution[10]. But we must believe – and model out – that in an alternative economic system where money creation methods are different and where debt finance is not as incentivised – that the better ways to do financing would emerge as the non-interest-based ones.

Let’s revisit the diagram we looked at earlier:

The core function that the banks and the funds/insurers play is “financing”. Getting money from those who have it to those who don’t and want to use it – and taking a broker cut in the middle.

There are two routes to doing that – debt-based finance and equity-based finance. The former happens via banks and the latter via funds and insurers.

In today’s world, debt-based finance is usually the more appealing “cheaper” option for most companies. Taking debt means you don’t lose your shares in the business and it also means that anything you owe of that debt, including interest, is deductible as expenses and therefore reduces your tax bill. Equity on the other hand is “expensive”. You can’t deduct that as an expense, and you’re going to be stuck with it permanently (unlike debt, which you can pay off). And if you want to sell equity you’ll normally have to deal with additional taxes such as stamp duty that don’t arise with debt.

Debt is also appealing to bankers (rather than using equity) because they can keep a meatier cut. If you raise money to provide home finance from investors – they’ll want a decent cut themselves. This reduces the banker’s margin. However, if you raise money from bank accounts, or savings accounts, the account holders are much happier to settle for far less returns (or in the current account – no return at all) safe in the guarantee that their account is FSCS protected (or equivalent protections across the world such as FDIC in the USA).

Practically this is how it plays out:

|

Type of capital source |

Cost of capital |

Rate of mortgage offered |

| Savings account | 3% | 6% |

| Current account | 0% | 5% |

| Interbank market | 4% | 5.5% |

| Investors | 6% | 7% |

As can be seen above, the cost of capital will determine the ultimate rates offered and banks always win as their cost of capital is the lowest (current accounts and savings accounts).

Additionally, because we are dealing with “electronic money” we’re now playing the favourite game bankers like to play in any case. Being able to lend out their newly-minted money is much better than having to take in £100 and then lend out exactly £100.

So the first issue with modern finance today is that both borrowers and financiers are very incentivised to opt for debt rather than equity.

The second issue is that interest is inequitable and creates perverse long-term inequality. We run a few arguments against riba in our article here and won’t replicate them here.

The third issue with interest-based financing is that you incentivise two lending behaviours which can lead to serious turmoil:

a. Banks are not as incentivised to diligence a deal as they might if their returns were directly linked to the deal succeeding. Instead, bankers are keen to finance a lot, for as much fees as they can get away with, and then to package up these loans and sell them to someone else. Effectively, because the bank is not directly exposed to any downturn in an asset or a transaction, the only thing they care about is the quality of the security. This leads us nicely onto the second issue.

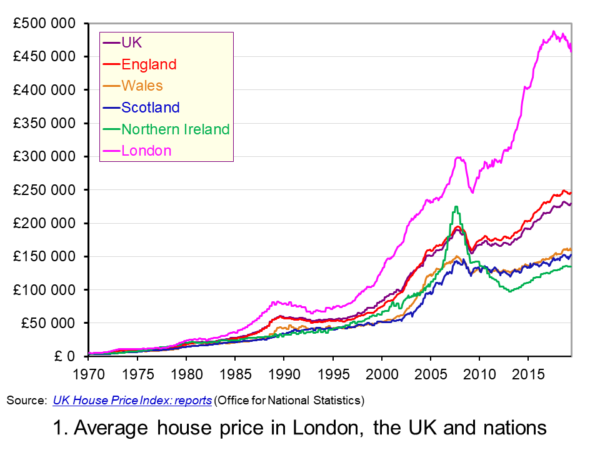

b. Because banks really like loans to be backed by a security, they particularly like backing those industries where there are sizeable and valuable assets that can act as a security. Houses are a classic example, and over the years the property market has dramatically spiked up in price disproportionate to the rise in salaries or even the wider economy. This then creates the effect of pricing people out of their own home – particularly in major conurbations like London:

[11]

[11]

There are probably more arguments to run here, but we think we’ve made the point: Interest-based financing clearly poses some significant challenges practically and ethically for society.

3. Derivative and uncertainty in transactions

We defined derivatives to include future, forward, options, swaps, CFDs, most forms of structured products and most forms of fixed income products.

We have already shared this diagram above:

Today, the value of the assets underlying derivative contracts is three times the value of all the physical assets in the world[13] and, banks carry “assets” on their books which consist mainly of claims on other banks, while their liabilities are mainly comprised of obligations to other banks and financial institutions.

We have divorced the real from the financial and increasingly it is unclear what the purpose of certain markets is other than as an enormous casino that give people a chance to become wildly rich if they learn the system.

This point is also closely linked with the issue with interest – derivatives need an underlying to bring them to life – and the two underlying assets of choice are debt and stocks.

We have already covered the wild spike in house prices since the deregulation. Here is the equivalent graph for the stock market. It follows a very similar story.

It is no great surprise that the two asset classes most underpinning the explosion of derivatives have themselves exploded in price.

So in our modern world, you become rich through holding assets that are popular with speculators, or you speculate yourself (work in finance), or, as a distant third, you do something entrepreneurial and add value to the world.

Let’s be clear, having assets has always helped throughout human civilisation. However, today having assets helps far more. In a recent report, Oxfam shared that the richest 1% pocketed $26 trillion in new wealth – nearly twice as much as the other 99% of the world’s population.

This creates a world where if you’re rich you’ll do just fine and probably get richer. But if you’re poor, you’re going to need a lucky break and incredible effort to break out.

But if you take away the massive speculation through derivatives you take away some of the unnatural juiced advantage that comes today from owning assets, you reduce financial speculation as a route to wealth, and you incentivise much more the route to wealth that we really should incentivise – good old-fashioned entrepreneurship.

4. No incentive to move to another system

Combining the three phenomena that we have sketched out – the privatisation of money creation, the prevalence of interest-based financing, and the rise of derivatives and financialization – and we have a situation where the world acknowledges something is very broken (Nicolas Sarkozy was calling for a total rethink of the financial system back in 2008[15], while Yanis Varoufakis has been calling for it more recently[16] but at the same time it is still completely rational for each individual country to stick with the current system.

Global finance is hugely interconnected, controlled by major financial institutions who owe no allegiance to a particular country. Global trade too is enormously interconnected and interdependent.

If any individual country decided to ban or reduce (i) the privatisation of money creation, (ii) the prevalence of interest-based financing, and (iii) the rise of derivatives and financialization, it would not be easy.

Any such move would take serious political capital to make it happen, it would cause short term pain, and, if it was not handled extremely carefully, it would potentially set that country back economically.

It is far, far easier to go along with the status quo.

This apathy, therefore, is the fourth issue we must tackle if we are to move from today’s financial system to a better one.

Issues with Islamic finance today

We have critiqued the modern financial system but we must now also turn a critical eye to modern Islamic finance.

We owe a lot to the pioneers of modern Islamic finance globally and it is on their shoulders that we build.

There are certain compromises and leniencies allowed by Islamic scholars during the early period which got the industry up and running. But Islamic finance developed in a different time and place and today is a completely different world.

What has unfortunately happened is that those early leniencies and compromises have crystallised and cemented such that today “market standards” and “market practice” has established around measures that were only ever designed to be stop-gap.

As we stated right at the start of this whitepaper, we believe the issues with the modern Islamic finance system arise primarily out of the following:

- The entire financial edifice they operate within is unislamic – and so any products the Islamic finance industry do come up with are blighted by inadequacies. (the “Edifice” issue)

- The Islamic finance industry has never really faced serious pushback from the constituency that matters most to them – their customers. (the “No Pushback” issue)

- There is a received wisdom within the Islamic finance industry that a “truly” Islamic product is just a mirage and the best way to structure an Islamic product is to start with a conventional product, and look to “Islamify” it (the “Conventional First” issue)

If we boil all three issues into one macro-issue, it is that there is no great vision and impetus to a better future. Modern Islamic finance is happy where it is.

We will of course sketch this “better future” out in the next section, however for this section I want to shed light on four manifestations of the Conventional First, Edifice and No Pushback issues within the Islamic finance industry. These should help clarify the challenge.

Sharia wrappers

First some background. Sometimes Muslims want to buy something that is not technically sharia-compliant. This might be a larger group of companies for example, where a few of the companies are not sharia-compliant. It might be that these non-compliant companies have too much leverage or have haram income that is more than just nominal amounts. It might be that a company is being bought by a Muslim shareholder majority company, but the target company needs to go on a transition journey from non-compliant to compliant.

Enter the “sharia wrapper”, a legal solution constructed by some practitioners and Islamic scholars over the last couple of decades. Effectively what this structure does is allow sharia-compliant investors to invest in something that is haram but at some level be able to consider what they are investing in to be halal.

The way this structure works is through back-to-back special purpose vehicle companies where your investment goes into Company A, which in turn passes it to Company B (through commodity brokers) and Company B is the entity that the haram investment is made from.

Through a series of complicated transactions, the overall effect is that of an investor investing x into a transaction with Company A, Company A entering into a transaction worth x with Company B and Company B investing an amount worth x into a haram investment. Once the haram investment makes a profit and wants to pass the profits back to the investor, the same process starts again until the investor receives the profit back from Company A.

The entire set-up is contrived and not liked by scholars. They will allow institutional funds to avail of these structures from time to time due to specific circumstances, however scholars and the AAOIFI – the global sharia standards authority – really limit the use of such a structure.

There are other “lighter” forms of sharia wrapper. When larger investors are investing into the USA or Europe (where there are fewer Islamic financial solutions) they will invest through master lease/sublease structures.

The idea here is that an Islamic investor is only buying the freehold (or master lease) and then they will sublease the asset to someone else entirely and charge a rent for it. The sublessee will then be allowed to get conventional finance for their sublease.

However, there’s a crucial move: the rent the sublessee pays the Islamic investor is actually just an economic arrangement to allow the Islamic investor to get the economic effect as if they had taken out the conventional loan themselves.

The fiqh argument is that the Islamic investor only holds the master lease and so is insulated from any direct involvement with the interest-based financing.This structure is of course less contrived, but still, in our humble view, problematic if relied upon as a permanent solution.

We understand that there are a few lines of analysis that some will use to justify such sharia wrappers:

- That if Muslims are to be able to invest in a globally diversified way, they need to be able to avail of conventional debt for certain investments that don’t really work without it, in countries where no Islamic debt alternative is found.

- That strictly structurally speaking, there is nothing impermissible taking place.

- That for larger institutions in particular there is a need to invest globally into those markets that can easily absorb their capital. The size of their capital would mean that Muslim countries are not appropriate as the sole recipients of their investments. And to participate in these wider markets, conventional debt is necessary.

- That Islamic debt finance is just not available and at the level of sophistication as mainstream finance, and so for many assets and investment strategies, the only option is conventional finance.

Argument (1) is not strictly true. Muslims can invest in real estate and companies across the world, but they won’t make as much return from their investments as if they leveraged them with debt. And there are enough Muslim countries where there is sharia-compliant debt available as alternative venues for investment.

Argument (2) is arguably true, but to our mind it seems to a very odd result of sharia rules to enable an investor to invest in a “halal” way into something that they couldn’t directly invest in. This should only ever be allowed as a one-off.

The reasons for allowing the transaction must necessarily derive from arguments (1), (3) and (4) otherwise we could “technically” justify anything.

Argument (3) is somewhat compelling, but it is somewhat undermined by two facts:

- If you’re an institution that is large enough, you can dictate terms to conventional banks and ensure you are provided with Islamic debt financing even in non-Muslim countries.

- If you’re not an institution large enough to dictate terms to conventional banks, then you’re probably not an institution large enough to argue that you must go abroad to deploy your capital. There are plenty of places to invest across the Muslim world and internationally in halal investments that don’t require conventional debt.

Argument (4) is also initially compelling. It is true that complex types of finance such as fund finance may not properly exist in the Islamic debt markets. However, we remain unconvinced that the world of investments is so narrow as to require an investment house to use such conventional finance products. Take the case of fund finance. It is used by private equity funds to boost their returns as it limits the amount of time that they use investor capital in an investment. This in turn means a higher internal rate of return (or “IRR”), which is the metric they are judged on. IRRs are linked to the time period an investment is held for, so PE funds want to reduce the time period by using an alternative source of finance. Bear in mind, that PE funds will be leveraging the actual investment itself heavily anyway – and that’s separate.

Additionally, having conversed regularly with people in the finance world, our understanding is, for the right price and with the right scale, one can get pretty much any type of financing in a sharia-compliant structure. This is increasingly so as well, as undeployed capital pools switch from the West to the Middle East and Asia.

Finally, is it a burning need for an institution to have to use niche forms of finance anyway? We’re not convinced they are core to most investment strategies – just additive.

Having said all of that, we could certainly see situations and reasons where scholars would allow sharia wrappers to be used for reasons (3) and (4).

So what’s the issue?

The issue is that in most conversations where a practitioner says to an Islamic scholar “please can we use a sharia wrapper because we really want to do this deal,” they are saying that because they come from a conventional finance background and are seeking to copy the mainstream system with an Islamic sign-off. They are not thinking from first principles “okay, I know Goldman Sachs do these transactions in this way – but how about I do it differently?” This is the Conventional First issue writ large. This then leads to unsatisfactory products (the Edifice issue).

Commodity Murabaha

The next major issue in Islamic finance today is the widespread use of the commodity Murabaha structure. This product is approved by the vast majority of Islamic scholars and it is one of the most-used Islamic product today. However, we note that a number of scholars also advise that, where possible, if another product structure is possible, it is better to use that.

The reasoning behind this is that commodity murabaha can, from some perspective, seem too synthetic a way of transforming a loan contract into a sale contract. The “commodity” at the heart of the commodity Murabaha is not really the economic aim of the transaction, it does not even move during the entire transaction, and the same commodity could be used hundreds of times for multiple different Murabahas with no issues. From a risk perspective too, the way that the entire transaction is organised, a financier takes on very little to no ownership risk over that commodity.

For a detailed analysis of how the classic commodity Murabaha structure works, see here.

We think that there are certainly situations where the use of commodity Murabaha makes sense – for example when operating in the UK or a non-Muslim country where tax and regulatory laws are such that they make the use of ijarah structures prohibitively expensive[17].

However, in Muslim countries too, commodity Murabaha usage is prevalent.

All too often, unless there is governmental intervention, it is very easy to just default to the commodity Murabaha product as a fix-all for everything. This is because the commodity Murabaha structure is malleable and versatile and can be combined and used to effectively solve any financial issue.

But when there is governmental intervention – such as when the Omani government banned commodity Murabaha – the industry figured out ways to manage their needs and started using alternative products instead. We understand and acknowledge that some may quibble about the execution of such changes, but these are logistical points, and we are talking right now on the conceptual level.

The overuse of commodity Murabaha and the sloth around innovating better products is in our humble view a key challenge for modern Islamic finance today. It is caused by a full house of the Edifice, No Pushback, and Conventional First issues.

Islamic banking

Modern Islamic banking is the third manifestation of the Conventional First, Edifice and No Pushback issues.

Modern Islamic banking today is structurally identical to conventional banking. The system is lubricated throughout by the use of commodity Murabaha to mimic the conventional banking system’s core planks:

- Fractional reserve banking (or, as the financially savvy would articulate it, a careful management and balancing of long-term assets and short-term liabilities.)

- The creation of private money

- An overemphasis on savings account, cash management, and treasury solutions rather than an emphasis on productive investment activity:

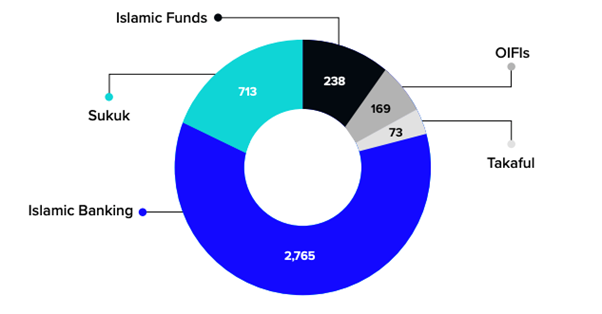

In contrast, if we add up overall global data we get:

a. Banking Assets: $183 trillion[19]

b. Bond market: $119 trillion[20]

c. Funds: $135 trillion[21]

As we can see, the spread is much more even in the mainstream than the Islamic industry, with a much heavier weighting towards public market investing (around 8.5x more in fact)[22].

As long as we stay stuck in a “rent-seeking” mindset rather than a “value-creation” mindset the global Islamic economy will not grow as fast as it could and the velocity of money circulating through the economy will remain lower than it should. Islamic banks are only partly to blame for this – this is also a matter of consumer tastes and investment appetites. Those too need changing.

A higher velocity of money circulation is a Qur’anic mindset too. God says:

As for gains granted by Allah to His Messenger from the people of other lands, they are for Allah and the Messenger, his close relatives, orphans, the poor, and needy travellers so that wealth may not merely circulate among your rich. (59:7)

30% debt ratio in public markets

It has become a very established norm in the public markets that Islamic funds are allowed to invest in companies so long as their income is less than 5% from haram sources, and so long as their debt is less than 30% debt/market cap.

There are a few different variants of this rule, but all basically meander around the same point: leniency to allow for a certain percentage of conventional leverage in the companies invested in. The origins of the rule make for interesting reading as covered by Mufti Faraz Adam here.

We have previously analysed totally debt free stocks here, and we found that it is possible to create a rather aggressive tech-leaning portfolio that is debt-free but not a particularly well-balanced one.

What has resulted is the rather odd situation where any Islamic fund out there has a sizeable number of its investments in companies that benefit from conventional leverage. Muslim pensions are being grown using conventional leverage but with the veneer of investing through an Islamic fund.

No incentive to move to another system

Like their conventional counterparts, Islamic financial institutions are all rational commercial organisations. Unless there is a clear reason to change, it is irrational and risky for them to change. Rather, it is better to keep one’s head below the parapet and align with the status quo.

The only realistic reasons a rational operator would have to change are:

- Customer demands

- Regulatory requirements

- Competitive environment

These rational reasons will play an important part in the practical roadmap we share towards the end of this whitepaper.

A new way of doing things

We now turn to setting out a sketch of what a (modern) Islamic finance alternative economy could look like instead.

This is not perfect, it is not deeply detailed, and it is not rigorously academic. But it is a starting point and coherently (we hope) sets out a practical roadmap to a reasonably well-articulated future world that we should all aim for.

There will be some things we have omitted either intentionally (for brevity) or because we are not wise or experienced enough to even think about it. There are other things we may well have just got wrong.

If you spot these, dear reader, then know that there is an open invitation to you to contribute in your extensions on this whitepaper and even corrections of it.

With that, let’s begin. We have two groups of interlinking solutions to propose:

- A new mechanics of money creation

- A scaleable alternative to debt finance

Ultimately, both solutions aim at doing the same things:

- getting rid of the ambiguities and opacity built into the financial system so that the risks and rewards are far clearer to us all.

- Aligning incentives to those activities that add most value to the world.

A new mechanics of money creation

As outlined above, today’s banks create “private money”. This accounts for the vast majority of the money supply in our system today (at least 80%[23] but could be up to 97%).

This is a serious problem because of the corollary effects also outlined above.

A simple way of addressing this situation is to revert to full reserve banking and to require all currency to be fully backed by a stable asset such as gold.

There are several issues with taking this route:

- Banks would not be able to issue out loans or do anything else with the money other than to hold it.

- There is not enough gold in the world today and the expansion of gold supply would now be linked to the rate of gold mining – an odd incentive in an era of climate change.

- The expansion of money supply being linked to something as arbitrary as gold mining makes it impossible for governments to control the expansion of money supply to more closely align with economic growth strategies.

- In our reading, there is nothing “sacred” about gold that would make Muslims prefer it over alternative solutions.

- Gold is ultimately itself not a productive activity, it is fundamentally a piece of metal that derives its value only from how much we humans desire it. In that respect its “value” derives from exactly the same source as fiat currency.

- Gold would also suffer from volatility, and previous experiments have resulted in stagnant economies[24].

We currently do not think a gold-backed approach is a viable model for an economy in today’s world. We may be wrong.

Instead, our solution closely aligns with those of Positive Money[25] who argue that private banks should no longer be allowed to create new money inadvertently, and a form of full reserve banking should be adopted instead. Their excellent analysis thoroughly covers the key moves needed for a full transition[26]. We do not replicate that analysis here, but strongly encourage readers to consider their material.

This does leave the small matter of how to issue new money into the system. Our views on this are that either:

- Under this new financial system perhaps we don’t need the issuance of new money at all, or only at a much-reduced rate. This line of analysis needs research we have not conducted here. Things to consider under this analysis are the effects of other financial systems of other countries around the world who do create new money for their economies and whether for our country (the country that first adopts such a system), not issuing new money would put our economy at a disadvantage.

- New money does need to be issued but can be issued by a variety of means directly by the government (e.g. a citizen’s dividend, infrastructure spending by the government, indirect financing to business (via banks), or reduced taxes). This is the Positive Money solution.

Building on the above, banks now earn a living by:

- Maintaining a transaction account for customers for which they can charge a fixed subscription fee and an ongoing per transaction fee (which they do anyway). Banks keep the money in these accounts entirely segregated and do not use them for any purpose.

- Lending. Banks not only maintain transaction accounts, they also have “investment accounts” where they explicitly agree with investors to use the money for a set type of investment and lending activity. Banks are now effectively a private credit fund. They can only lend out the money they have taken in from investors and nothing more. If something goes wrong, both the bank and customers lose money – but the transaction account money is not affected at all.

- Ancillary services that banks can white label and sell on (e.g. insurance).

Neither the transaction account nor the investment accounts need to be “guaranteed” by the government as they are in many countries today. The transaction account need not be guaranteed because by law the bank cannot use it anyway so the money is just always sat in a central bank account ready to be extracted when needed.

The investment account need not be guaranteed because when you make an investment, you have to face up to the risks and the rewards. Without full exposure to risks and rewards, the incentives of the parties are distorted, resulting in poor investment decisions and moral hazard, build up of instability, and then, an eventual disastrous correction (this is the story of most bank runs and subsequent bank crises).

Ultimately the pieces are then picked up by taxpayers and everyday folk – the people whose money was at risk in the first place. The people who most profited simply walk away.

What the steps outlined above do is effectively route all money flows from people with money to people who need money via the investment markets rather than via banks. The new “investment accounts” banks set up are simply another player in the investment markets.

The role of the bank as a transaction account provider is now simply that of a service provider for which we pay to use their facilities.

For all banks, including Islamic banks, there are now clear incentives to move away from “rent-seeking” activities into “value creation” activities – as that’s how they will need to make money now. Gone are the days where they could collect in deposits from customers and pay them £0, and then take those same deposits and park them with the central bank and make a 4% interest return on them[27].

This change will also be vitally important in the growth of private companies that use no debt or only sharia-compliant debt, and growing them to the point they become publicly listed. If we are to realistically move away from the 30% debt rule when it comes to public market investments, we need to create a viable universe of alternative companies.

A scaleable alternative to debt finance

Debt financing isn’t always a bad thing – just not too much of it

Critics of the modern financial system and the modern Islamic banking system rightly criticise debt finance and its prevalence as one of the key malaise of our times. Rightly so. But an Islamic and more successful solution need not wipe out debt finance.

Debt finance is not an “unislamic” or “unethical” thing. Indeed, most of the Islamic transactional structures used today in Islamic finance and approved by the AAOIFI standards are based on debt financing. There are also clear differences between debt finance and Islamic debt finance as outlined by Mufti Faraz Adam in a recent post.

But the reality is Muslims are very upset about debt finance – including Islamic debt finance. And they do have a point.

The links between debt issuance and money creation, together with the hegemony of debt financing over other types of financing is what causes us to confuse between debt financing as a fundamentally value-neutral tool and the effects of its overuse. It is this hegemony of debt (including Islamic debt) and its links to money creation that are the real root causes of our upset.

Too much of something is never good – however we mustn’t now also swing to the other end and say “debt finance is always bad”.

And remember, with the fundamental changes proposed to the way money is created in the previous section of this whitepaper, the profit motivations of the key issuers of debt have already materially changed.

Let us revisit a table we looked at earlier:

| Type of capital source | Cost of capital | Rate of mortgage offered |

| Savings account | 4.5% | 6% |

| Current account | 0% | 5% |

| Interbank market | 4% | 5.5% |

| Investors | 6% | 7% |

Current accounts as a free source of money would now no longer available. This would have previously netted a bank circa 5% which is an extremely health margin. Additionally, for each £1 that is put in a current account, banks could lend out much more than that due to the multiplier effect (up to 10-20x). This again would help magnify up returns tremendously.

In absence of that, banks now get funding from much more expensive sources, and their margin is much tighter.

But if a bank is already set up to operate a 5% margin (or a magnified version thereto), they will rationally look for better yielding activities than these tight-margin loans.

Rational decisions at this point would include:

- Exploring higher risk (but also far more productive and higher margin) SME financing

- Exploring equity investment where the long term capital upside will align with the higher margins banks were previously getting

- Look to build up enormous scale so that the lower margin activities are still profitable

The point is that an artificially cheap and guaranteed zero—cost source of capital incentivises low-risk, rent-seeking behaviour, securitising safe assets (such as property) and ignoring the most productive (but higher risk) activities. Because – why take the risk?

A similar dynamic is seen today in the conventional finance world with the rise in interest rates. Central banks know that this will encourage people to keep money in the bank, which dampens economic activity, which slows down growth, and ultimately reduces inflation. You give someone low risk guaranteed returns, and I’ll give you a long-term low-growth and stagnant economy.

Change accounting and tax treatments of equity

In today’s world, debt-based finance is usually the more appealing “cheaper” option for most companies.

Taking debt means you don’t lose your shares in the business and it also means that anything you owe of that debt, including interest, is deductible as expenses and therefore reduces your tax bill.

Equity on the other hand is “expensive”. You can’t deduct that as an expense, and you’re going to be stuck with it permanently (unlike debt, which you can pay off). And if you want to sell equity you’ll normally have to deal with additional taxes such as stamp duty that don’t arise with debt.

In an Islamic system that inclines towards risk and reward sharing where possible, these regulatory and tax changes would be quickly made.

So now, as a company considering your options you have either:

- A more expensive debt option than before (reflecting the earlier changes we made to the money creation mechanic and the banking system)

- A more tax-friendly equity option than before.

We would anticipate more businesses would start going for the equity route than before.

Reduced use of Sharia wrappers and commodity Murabaha

The above changes will naturally impact the Islamic banking sector. Now that debt finance and risk-free returns are not on the table, we would anticipate that equity financing and higher margin investments become far more popular with Islamic banks just like with conventional banks. Secondary markets would now also start leaning towards trading more equity-based instruments.

However, whilst these structural and systemic changes do make debt-financing a less appealing route, where debt financing is used, the changes themselves do not make it any more or less likely that an Islamic bank would use sharia wrappers, the 30% rule and commodity Murabaha.

For this we will need customer pressure along with regulatory and governmental intervention to set clear parameters around their usage. Islamic scholars will need to be firm with the companies whose sharia boards they sit on that if better structures are available the companies must give preference to those.

We anticipate this will need some learning and unlearning on the part of some in the Islamic finance industry, however, other than tax and regulatory reasons, for the vast majority of Islamic financing transactions, we are dealing with a simple asset like a house, a factory, or a car. We see no reason why more palatable structures such as ijarah or diminishing musharakah may not be used in these situations.

There will be other ways to get financing and money flowing through the economy

Critics may well ask if equity financing is always right for certain types of businesses – and it may not be.

Under our vision, debt finance is not precluded and will still be available. However, it won’t be as plentiful.

So a critic may argue that this amounts to the same thing. Not enough debt finance available for a type of business that really only needs debt finance.

To this we would remind the critic that under our vision, the government will also be injecting cash (new money) into the economy itself through various means. Some of these may well include investing directly in key infrastructure and industries that require patient dept finance (e.g. climate-related technologies and plants).

Additionally, there is nothing stopping the government creating the money and then giving that money out (without the power to create further money on top) to the banks who will then distribute out that money through means of debt finance and take their cut.

We are not against debt finance and appreciate the need for it – we are just against its hegemony and it being tied up to money creation in private hands.

Equity and rental financing

We would anticipate that equity and asset rental financing would become the prevalent types of financing for many larger transactions.

These types of transactions do not attract as much zakat (with equity investments only attracting zakat on the cash and liquid assets and rental property only attracting zakat on the rent – not the value of the property).

This goes to show a wider economic incentive built in naturally to the Islamic financial system. Islam wants to encourage as much productive activity as possible as opposed to having too much stagnant cash in the system.

Cash should be reduced to a lubricant for substantive and useful enterprises to take place, rather than become the object of business itself.

This point is reflected in the famous narrations:

“The best of people are those who are most beneficial to people.”

(al-Mu’jam al-Awsaṭ 5937)

And

“The most beloved people to Allah are those who are most beneficial to people.” (al-Muʻjam al-Awsaṭ 6/139)

Somehow a narration that said “the best of people are those who undertake the highest margin arbitrage” doesn’t have the same ring to it.

Arbitrage transactions (where you effectively buy at a cheaper price and sell at a higher price) necessarily come about because you’ve discovered some inefficiency in market pricing. So there is a benefit to undertaking trades like this in many cases as it helps with the market’s price discovery.

But, when all is said and done, if you’re literally doing nothing of value in a transaction, then, though it might not be haram, one does have to ask oneself “what’s the point?”

In fact, there are some instances where brazen no-value-add arbitrage is prohibited. Taking advantage of someone’s ignorance or necessity to make an unduly large spread purely because of their ignorance or necessity is actively forbidden.

“The Prophet (PBUH) said: “Do not go out to meet the riders (in a trade caravan).” (Muslim)

The Prophet forbade traders from riding out to incoming sellers and transacting with them outside the city before they have a chance to get into the market and discover the actual price of what they have to offer.

In this case, the traders who were riding out were looking to buy the goods from the foreign traders on the cheap, and then return to Madinah and sell it at the market price. Their “value-add” here is almost non-existent.

We would hope and anticipate that with the changes discussed above, as well as a willing regulator, arbitrage investments will reduce and the focus will increase on more productive investment types.

Practical Roadmap to Financial Heaven on Earth

Let us now turn to the practical playbook that could deliver us financial heaven on earth.

In this section we outline the key steps that need to be strung together to deliver lasting change. This section is a strategic gameplan and so we must approach it with a degree of flexibility and be ready to change and adapt as the practical reality changes.

Show alternative structures that work

The first step in our journey is to show that an alternative is possible. Without showing this, you are calling to a theoretical construct, not a practical future.

We will need to show alternative structures for each of the following:

- The bread and butter of finance

- Investments

- Insurance

These building blocks are combined in various ways to deliver more complex financial products and so showing that we can deliver these is a vital step in persuading practitioners that an alternative is possible.

The bread and butter of finance

Finance helps lubricate the purchase of larger transactions – particularly homes. Finance is also essential for the accelerated growth of businesses through various specialised forms of financing that that necessitates.

In both these cases there are now very well-established Islamic models that enable financing to reach those who need it.

In particular, there are a series of innovative home financing products currently being worked on in the UK by the likes of Wayhome, Primary Finance, and (our partner) Strideup. These products not only provide financing for home buyers, they also add an equitable aspect to the whole transaction that materially changes the transaction into one where both sides are on more equal footing.

What these products show (to varying degrees) is that you can create regulated Islamic financial products, that are scaleable, that have liquidity, that can be securitised, and are appealing to customers.

For business finance, wherever there is an asset involved it is relatively simple to engage in a sale and leaseback structure. So for businesses looking to finance raw materials, machinery, and land purchases, the pathway is straightforward and already well-used in the mainstream trade finance world.

Where there is no asset, things get a little trickier. Here, murabaha transactions usually do enable us to get to the desired outcome in the end, though we consider there could be scope to ideate around a human capital financing model for asset-light businesses that could prove a better alternative to the Murabaha route.

Investments

The Islamic investment landscape has matured over the last few decades. In the public markets there are now well-established methodologies to enable halal stock funds to be constructed.

In the sukuk space, there are a wide variety of sukuk to choose from and multiple types of sukuk that have been issued.

The Islamic world has always loved real estate, and most types of real estate investing have been structured Islamically by this point.

Venture capital is inherently Islamic and the small amount of tidy-up that was needed has now been done and Islamic venture funds are now springing up. As early pioneers in this space, we’d like to think we’ve had a small hand in this.

Cryptocurrency too has seen (generally positive) scrutiny from Islamic scholars and approval and adoption by the Muslim masses.

Private equity is an investment strategy that has only seen patchy Islamic finance applications to date. This is because mainstream private equity practices require debt finance. However, that too is now changing with a new wave of sharia-compliant private equity funds in the works who purport to realise the equivalent returns of involving financial leverage through other types of (non-financial) leverage.

Where Islamic finance has not come up with many alternatives is in the derivatives space. Some work has been done to facilitate sharia-compliant swaps and hedging facilities, however the nature of derivatives is so antithetical to Islamic financial law, that this is not necessarily an area where Islamic finance needs to, or should, have an answer. Instead, Islamic finance would be keen to remove most derivatives from circulation.

Insurance

The Islamic insurance model is close the to the cooperative model and has been successfully implemented across the Gulf, Malaysia and Pakistan.

Islamic reinsurance is also an established industry and the full gamut of insurance products are now available in a sharia-compliant manner.

Muslim and non-Muslim AUM to back it

As should be clear from the brief overview given, there are a plethora of Islamic product structures out there.

But are there as many in the mainstream? No.

Are the Islamic products as high quality as we would like? No.

We need to get to scale for our voices to be taken seriously and for us to build better products. In investments and finance, one ultimately needs to be operating at a scale of billions in order for true product innovation to take place.

Muslim Assets under Management (“AUM”) is important as it is likely to be the first mover once an Islamic product is half-decent and viable. However, Muslim AUM is largely controlled today by Islamic banks. And, as we saw previously, Islamic banks have parked most of that money into rent-seeking, lower-productivity investments. This huge pool of AUM is not properly making a profit nor is it properly supporting an entire ecosystem of investment that it could and should.

And then there’s the other big AUM problem.

The largest sources of AUM that could be potentially sharia compliant are currently supporting non-Muslim businesses. These are the large Islamic sovereign wealth funds.

This is a tragedy that has stunted the growth of the Islamic investment industry.

Western firms are falling over each other today to secure investment from the Middle East, however the biggest sovereign and private institutional investors in the Middle East have little interest in Islamic investment principles and do not make this a requirement to transact.

If they stressed to these Western firms that they only invest in sharia-compliant investments, overnight we would see an enormous explosion of sharia-compliant investment opportunities.

We can learn a lot from the ESG story (Environmental, Social and Governance-focused investments).

ESG investing is a key criterion for many large Western investors and they actively make investment decisions based on this. International investment houses have quickly cottoned on, and huge swathes of investment products today are ESG-focused.

But ESG investment funds only get off the ground if you have larger anchor investors willing to back such a fund and get it up and running. Only then can everyday folk gain access.

But if Muslim institutional investors that should be facilitating are not facilitating, the task becomes that much more difficult.

Without the Islamic Bank Muslim AUM and institutional Muslim investor AUM, Islamic financial products can’t reach scale and can’t be as innovative and cost-effective as mainstream products. This precludes most non-Muslim AUM as well. They would much rather use the better product as they have no issues with riba.

Muslim retail pressure on Islamic banks

This brings us nicely onto our next port of call.

Islamic banks face no real incentive to change until customers demand it. We need to tell them to

- improve their customer standards

- upgrade their product offering and not just park AUM into rent-seeking propositions

- not use fractional reserve banking

- move away from an overreliance on commodity Murabaha

- become more transparent about fees and sharia approvals

Only once we do that are Islamic banks impelled to change. And change Islamic banks we must – it is either that or we must convince their customers to leave and do business with more on-mission startup fintechs.

Pressure on Islamic central banks to adopt new money creation mechanisms

In our proposed multi-year campaign let’s say we have now innovated on Islamic products, got Muslim and non-Muslim adoption, convinced several large Muslim sovereign wealth funds to invest in line with Islamic principles and the early signs of success are showing.

What we must now do is to convince the central bank and government to make serious and necessary changes to our financial system in order to break it out of the cycle of boom and bust and debt over-issuance and debt over-contraction.

We won’t repeat the points already made in the section on money creation above, but it is these that we need to be advocating for.

Prove model and incentivise RoW to adopt it too

Once an Islamic central bank has committed to an Islamic economy and started to execute on that vision, we are firmly on our way to realising the modern Islamic economy ideal.

However, the work is not done yet. It is not good enough to realise a modern Islamic economy; it is also vital to show that it works as well as, if not better than, the conventional financial system.

We anticipate it will take several years to make this case, but then, we would dream that non-Muslim nations also started to adopt our economy’s structure. That, truly would be da’wah.

Concluding Thoughts

This is our broken, unqualified effort at diagnosing the problem and articulating a practical roadmap. We have done it, to get the conversation going.

We would love to invite investment managers, policymakers, bankers, central bankers, regulators, academics to pick up this thread and expand, criticise, tweak the ideas set out above.

There are a whole host of related issues we have not explored here for sake of brevity but would be worthwhile examination topics, such as :

- US Dollar hegemony, CBDCs and a global currency

- By pushing money creation to the hands of the government, have we not just pushed the problem further upstream and now instead of banks defaulting, countries will default? And then bailouts will come from other countries which comes with its power implications.

- Deeper analysis into the nature of riba from classical sources and what those teachings have to say about the shaping of the modern economy

- How a taxation overhaul to the treatment of debt would work

- Are there any regulatory constraints Islamic banks operate under that will need to be addressed before they can properly start deploying their AUM into more productive areas?

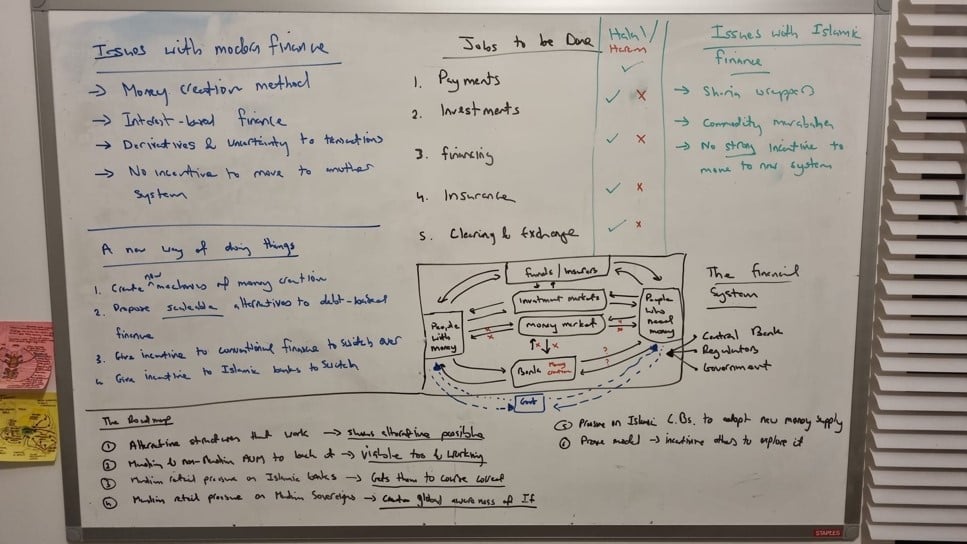

For those who like squinting at whiteboard sketches, here’s this entire article in diagrammatic form:

References & Notes

[1] We use the word “truly” in quotations as we don’t want to imply that the current Islamic finance industry is unislamic, but the word “truly” nicely encapsulates what we’re driving at.

[2] See https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210310005386/en/Global-Financial-Services-Market-Outlook-2021-2030-Expected-to-Reach-28.52-Trillion-by-2025—ResearchAndMarkets.com and https://statisticstimes.com/economy/projected-world-gdp-ranking.php

[3] Thomas Philippon (Finance Department of the New York University Stern of Business at New York University). The future of the financial industry. Stern on Finance, November 6, 2008.

[4] https://www.statista.com/statistics/248004/percentage-added-to-the-us-gdp-by-industry/

[5] Simon Johnson and James Kwak, “13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown,” (New York: Pantheon Books, 2010)