Why is Interest Haram? Why Does Islam Forbid Interest?

Ibrahim Khan

Co-founder

8 min read

Last updated on:

“Why does Islam forbid interest?” That’s a question we have all asked or been asked at some point in our lives.

Usually it leads to a headache, the discovery that a close friend is actually secretly a raging capitalist/socialist (replace as per your political proclivities), and – the worrying one – doubt about one’s religion and moral code.

The good news is that there are some sensible, clear answers to the question.

The bad news is that there are some (nearly as) sensible, clear answers to the answers.

However the really good news is that a novel approach struck me during some recent research that I was doing for an article on the nature of money (it is a high octane life we lead here). The approach is a simple, logical argument which doesn’t require detailed knowledge of the Qur’an and hadith on the topic.

But, in order to get to the argument (in a follow-up article to this one), I need to lay the groundwork with an analysis of the usual answers that we can give.

Interest is exploitative (Argument 1)

Standardly, the argument against interest is that it is exploitative. A rich person is one who has lots of money, and he is in a position to lend. A poor person has little money and is in need of a loan. If he takes out an interest-bearing loan, the net transfer will be from the poor to the rich, which is counter-intuitive and exploitative on all but a really hardline analysis.

But what about the case of a doctor who earns £100,000 a year, who wants to take out a mortgage and pay £1000 a month for 25 years, and own his house at the end of it, rather than £1000 a month in rent for 25 years and own nothing at the end of it? The bank benefits and the doctor benefits – that doesn’t seem exploitative right?

What does one do in such cases where it is not (prima facie) exploitative? Well, then one makes the move that in general it is exploitative.

But what if, in our modern context, interest is arguably not even generally exploitative? Some people say that an interest-bearing loan can lead to a lot of growth for a business, or can (as the above example outlines) allow one to get onto the housing ladder and pay less money than they would if they were to rent.

These people are not correct in my opinion (and Argument 1 is fundamentally a very good argument, particularly for fractional-reserve banking economic model (that may require another article to fully unpack)), but it is obvious that if we are to say “interest is exploitative”, we invite counterattacks that say “here is an example of where interest is not exploitative”. So I don’t feel this is an argument without a comeback.

Money is only a means of exchange (Argument 2)

Another line that attempts to cut off any such counterattacks is: “money is simply a means of exchange, and as such Islam does not allow for a thing which in of itself has no value (and is not the objective of the transaction) to be ‘rented’”. The point being made here is simply that we don’t ever go to a shop to buy £5 notes to use as cooking stock, or 50p coins to use as a nail file. We like money because it buys us nice things, not because that piece of paper is really useful itself.

So here any “interest-is-not-exploitative” arguments become irrelevant – as we’re not arguing that interest is exploitative or not in the first place.

One could argue that interest is simply a compensation for usage of money during the term of the loan. I lend you £100 for 2 months; I consequently don’t have access to my £100 for 2 months and should be compensated for that loss of opportunity.

But the proponent of Argument 2 would argue that Islam simply doesn’t allow something like money to be rented. However, then the related question arises: does Islam allow the time-value of an item (the opportunity to use x thing) to be charged for in any case?

The answer to that is yes. One can obviously rent things (my flat for example). One can also charge a different price for deferred payment of a good.

So we’re allowed to “rent” things, just not money (and any item which is used as an alternative to money, such as gold coins back in the day).

But why is that? Well, to understand that, let’s have a look at what we’re “renting” out when we rent out money. Money is a store of value. That is the key quality of money. If one has renting out a gold coin (somehow back in vogue as a currency let’s say), we wouldn’t want the gold coin for itself, but for what nice things it could buy.

On the other hand, a gold wire made out of the same amount of gold for use in a certain circuit, could, by a bold scholar, be argued to be valuable intrinsically. Renting out such an item would then be allowed, as the thing being rented out is the usage of the creation that took a great deal of technical skill and know-how to create, not just the raw gold material.

This is a much more solid argument and lies at the heart of the Islamic prohibition on interest. It’s not that Islam forbids us making money, it’s that Allah has forbidden making money from things which are intrinsically useless.

The New Argument

So what is the problem with renting out a store of value? Well, what is this value that we are storing? The value in a £10 note is that which we are willing to give it. If our confidence in the acceptability of the £10 wavers, then our confidence in the £10 will crumble. The thing that gives value to the £10 is its widespread acceptance and our knowledge that we can use this intrinsically worthless little piece of paper to buy things that are intrinsically precious.

So we’re renting out “confidence of many others in society”. I don’t like that – and that, I think, is ultimately why interest is haram.

There are two problems with renting out the “confidence of many others in society”. Firstly, there is a deal of uncertainty in this transaction, one cannot really specify what levels of confidence are running at, at the time. This is problematic as Islamic law prohibits “gharar” (uncertainty) in a transaction and it also requires the asset at the heart of a transaction to be clear and distinct (which “confidence in many others in society” is not really).

However, ultimately, I think we may be able let this slide, as levels of confidence may not be relevant beyond a certain point. For example, when we borrow money we want to know we can buy our grocery or house with it, but we’re not necessarily interested in a Moody’s or Fitch level analysis of the credit risk profile of the country’s currency.

Also, clearly one can price interest – it goes up and down with demand and supply – so an argument could well be made that you can actually approximate confidence levels at any time

The second problem with renting out the “confidence of many others in society” is much harder to get around: this immaterial thing “confidence of others” that we are renting out, is not something we have a right to rent out.

This is because we don’t really “own” the confidence of others in society. Let us say we add our own confidence to the currency – given we are just one of millions – our contribution to the value of Pound Sterling is negligible. So why then should a bank (or indeed anyone) be allowed to rent out the combined “confidence of others in society”?

One could also argue “hang on, aren’t brands also all about deriving their value from what many others in society imbue into them? Isn’t Nike worth more than an unbranded pair of trainers?” Yes this is true. But the key differences here are (1) Nike trainers are an intrinsically valuable object that people buy to use for itself, while money is not such an object, and therefore one can set any price that the market is willing to pay as what we’re paying for is the good itself, not the confidence others have in it; and (2) Nike trainers are being sold by the owners of Nike trainers. If, however, one was renting one’s Nike trainers from a friend, one would not have the right to sell them. That is what is happening with money, so goes my argument.

As an aside, I think this argument also speaks to the power dynamics in society, wealth distribution, and what role the state has to play in monetary policy (and money creation) – but my thinking on this tangent has not fully developed yet. If you guys have any bright ideas on this front – please feel free to share.

A further thought to add to the mix:

People value and have confidence in money to buy things – they are focused on the intrinsically valuable things they can buy. By “renting out” money, i.e. by charging interest, one actually detracts from that confidence slightly, as you are using that money not to buy/sell things of intrinsic value, but of no value. You are also asking for more money back, which will require more money to be created in the economy as a whole(or more debt), and as such, you are cheapening the value of money, and therefore weakening the confidence of people in that money. So the very act of lending out on interest corrodes the value of that currency.

Finally..

While the above line of argument is an interesting and potentially promising line of analysis, it is admittedly very theoretical and may or may not succeed. For me personally, a sophisticated form of the “interest-is-exploitative” argument 1 of this article is still my go-to argument when people ask me “why is interest haram.” As ever, I’d be interested to hear what your go-to arguments are, whether you are convinced by the above, and/or if you can think of any way of rebutting/supplementing it.

But as ever, I’d love to hear your thoughts on the above and any alternative arguments you have found useful.

For more information on other key Islamic Finance topics, check out our Islamic Finance page here, and if you’re looking for some riba-free investments, head over to Cur8 Capital.

Comments (0)

Related Articles

View all

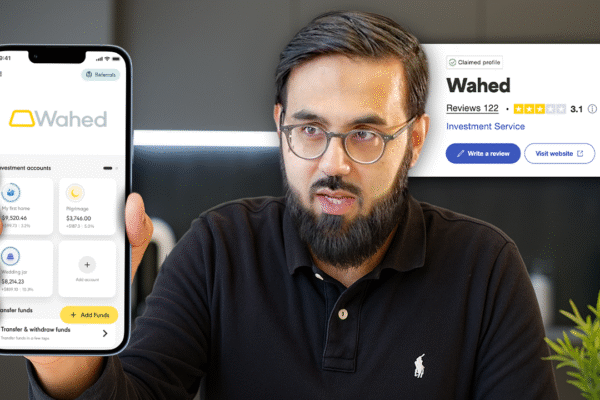

Wahed Invest – A Detailed Review & How to Use It (2025)

24 July 2025 15 min read

The Fall of Riba in the New York of Ancient Arabia

21 March 2025 4 min read

Leave a Reply