6 Wealth-Building Lessons from Khadijah (RA) Every Muslim Should Know

03 December 2025 8 min read

Ibrahim Khan

Co-founder

15 min read

Last updated on:

As Muslims running a business – particularly one where we are working in the Islamic economy – it has always felt slightly uncomfortable to us that we are ultimately competing with other Muslims.

From a secular commercial lens, the objective of competition is clear: to win.

The prize is a bigger market share and more profits accruing to the winner. But that message can sit uneasily when working in the Islamic economy or charitable sector and when your competitor is called “Muhammad” or “Fatima”.

The issue is a pressing one too – like with every Ramadan – this Ramadan saw a few haymakers thrown in the charitable sector where competition can bubble over to boiling point in the holy month.

So, in this article we seek to pull together the Qur’an and hadith references that shed some light on how exactly Islam views competition – and if and how we should engage in it.

We cover:

The Prophet said:

Avoid suspicion, for suspicion is the gravest lie in talk and do not be inquisitive about one another and do not spy upon one another and do not feel envy with the other, and nurse no malice, and nurse no aversion and hostility against one another. And be fellow-brothers and servants of Allah. (Muslim)

The verb “to compete” in Arabic can also carry the meaning of “to feel envy”, and clearly this hadith forbids that.

We might accept that this hadith is not talking about competition, but what about verses like this one:

Know that this worldly life is no more than play, amusement, luxury, mutual boasting, and competition in wealth and children. This is like rain that causes plants to grow, to the delight of the planters. But later the plants dry up and you see them wither, then they are reduced to chaff. And in the Hereafter there will be either severe punishment or forgiveness and pleasure of Allah, whereas the life of this world is no more than the delusion of enjoyment. (57:20)

Here the overarching message is that this is not the sort of competition that a Muslim should be engaging with and anyone who does engage in this sort of competition is at best wasting their time and at worst leading a life that will lead to punishment.

However, notice that even here that this pursuit is not in itself forbidden – it is the wrong framing of the pursuit – as an end in and of itself – that is the things being criticised.

So yes, Islam is very critical of certain types of competition or envious behaviour, this is not a blanket ban.

Indeed, the sharia explicitly clarifies that the Islamic economic system is one of demand and supply and competitive price discovery:

Prices rose during the time of the Messenger of Allah, and they said: ‘O Messenger of Allah, prices have risen, so fix the prices for us.’ He said: ‘Indeed Allah is the one who sets prices, the Restrainer the Extender, the Provider. And I am hopeful that I meet my Lord and none of you are seeking (recompense from) me for an injustice involving blood or wealth. (Ibn Majah)

The Prophet not only refused to fix prices, he made sacred the activity that results in the discovery of prices – trade.

The hand of God guides markets and sets prices through the dialectic of demand and supply delivered at the hands of traders.

And to try to set prices in any other manner would result in an injustice – as the end of the hadith nods at. Setting prices by a single individual is simply not a viable option given the almost impossible amount of complexity in an economy and supply chains.

Traders and open market competition is therefore an incredibly vital and useful mechanism through which we humans parse down information, our desires, and our views of the world into one tidy live market price.

The point is also clearly made in another verse:

O believers! Do not devour one another’s wealth illegally, but rather trade by mutual consent. And do not kill ˹each other or˺ yourselves. Surely Allah is ever Merciful to you. (4:29)

Trade, through mutual consent (i.e. dynamic price discovery between the parties) is actively encouraged in the Qur’an.

Great – we now know some kinds of competition are allowed – but we haven’t really got into the really sensitive types of competition that we want to figure out.

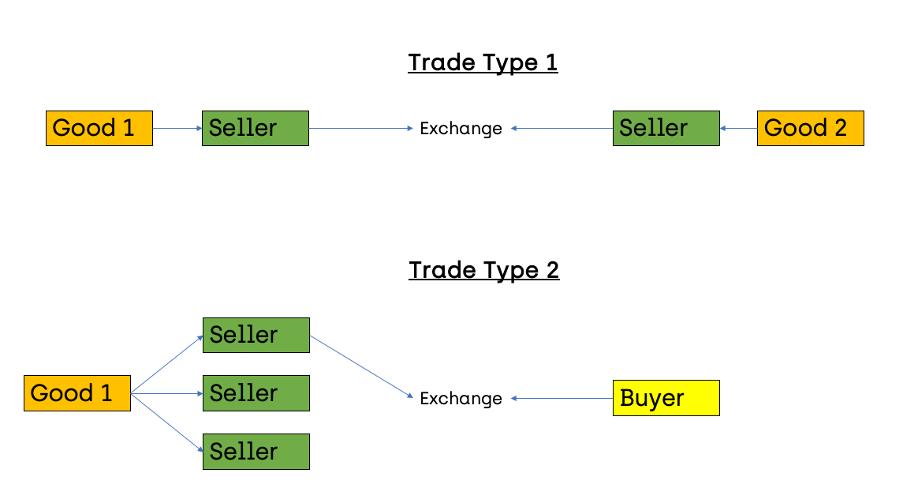

Let’s put it another way. So far, we have outlined that Islam likes free trade, buying and selling, and see transactions as a way for people who have something but want something else to engage in a just and fair exchange with someone where they each come away a winner.

Let’s label this Trade Type 1.

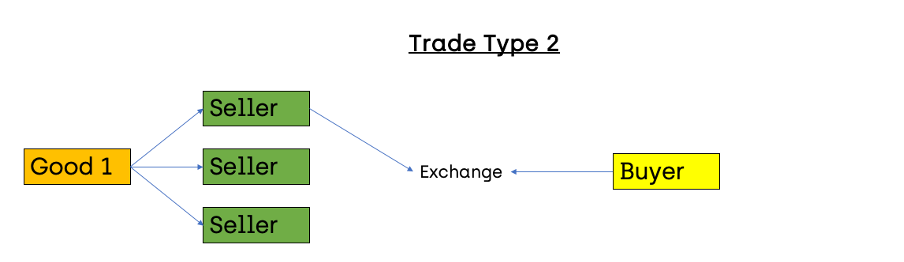

However, as all businesspeople know, there is also a Trade Type 2.

You are one of a long line of market stalls selling fruit, and the buyer is only going to go to one of you or your colleagues. The buyer goes ahead and fixes a deal with one of the sellers, and the other two sellers lose out.

Here the sellers are competing with each other to sell a similar or identical good.

What does Islam have to say about this, more intense, competition?

The Qur’an says:

So compete with one another in doing good. Wherever you are, Allah will bring you all together ˹for judgment˺. Surely Allah is Most Capable of everything. (2:148).

In another surah, Allah dramatically describes paradise and then says:

So for this let the competitors compete. (83:26)

Competition is often a zero-sum game where someone is going to lose out entirely or come second best, and the kinds of competitions Allah encourages Muslims to engage in are those where the thing being competed for is a “good” thing.

Tabari nicely outlines the nature of “competition” in his analysis of these verses. He says that competition has multiple participants and a desirable goal, where the participants want to achieve that goal to the exclusion of others, and where significant amounts of effort and sacrifice are needed to be able to win.

This “goal” needs to be worthwhile and productive to society. In the Quranic context the goal is the ultimate good: paradise. But the concept comes up in a more mundane way in the hadith too:

The Prophet said: “Competitions with prizes are allowed only in camel racing, horse racing, and shooting arrows.” (Ibn Maajah)

The scholars explained that the Prophet specified these activities because they are skills used in warfare and so have a broader purpose and benefit to society than just the competition.

The seerah of the Prophet is full of examples where the Companions of the Prophet would compete to do good.

For certain battles the Prophet asked for donations from his Companions. There is the famous incident of when Abu Bakr donated his entire wealth in response and Umar donated half his wealth. In that same period, Uthman ibn Affan came to donate 1000 dinar to the cause which caused the Prophet to say:

ما ضرَّ عثمانَ ما عَمِلَ بعدَ اليومِ

“Nothing Uthman may do after today will harm him.” (Tirmidhi)

In another incident the Prophet again threw out a competitive challenge to his Companions:

مَن يشتَري بئرَ رومةَ فيجعَلُ فيها دلوَهُ معَ دلاءِ المسلمينَ بخيرٍ لَهُ منها في الجنَّةِ

“Who will buy the well of Rumah and dip his bucket in it alongside the buckets of the Muslims, in return for a better one in Paradise?” (Sahih Nasai)

Uthman responded once again. He was a successful competitor “for good”.

We now know that Islam (a) allows competition; and (b) requires that the nature of the thing being competed for be “good”.

But what does that mean for me as an entrepreneur day-to-day?

Make sure you are earning a halal living and you’re not engaged in an industry that is morally dubious.

Then, thinking more broadly, try to engage yourself in sectors of the economy that are fundamentally productive and add value to the world either through the provision of goods and services that are fundamental to the happy functioning of society.

Things to avoid here would be working in (or serving) “sin” industries like tobacco, alcohol, gambling, certain defence manufacturers, certain banking and finance jobs, and derivatives-based jobs. Even working in frivolous areas of the economy such as gaming may be suboptimal.

There is a beautiful hadith where the Prophet showed his entrepreneurial side:

A man from among the Ansar came to the Prophet and begged from him. He said, “Do you have anything in your house?” He said: “Yes, a blanket, part of which we cover ourselves with and part we spread beneath us, and a bowl from which we drink water.” He said: “Give them to me.” So he brought them to him, and the Messenger of Allah took them in his hand and said, “Who will buy these two things?” A man said: “I will buy them for one Dirham.” He said: “Who will offer more than a Dirham?” two or three times. A man said: “I will buy them for two Dirham.” So he gave them to him and took the two Dirham, which he gave to the Ansari and said: “Buy food with one of them and give it to your family, and buy an axe with the other and bring it to me.” So he did that, and the Messenger of Allah took it and fixed a handle to it, and said: “Go and gather firewood, and I do not want to see you for fifteen days.” So he went and gathered firewood and sold it, then he came back, and he had earned ten Dirham. (The Prophet) said: “Buy food with some of it and clothes with some.” Then he said: “This is better for you than coming with begging (appearing) as a spot on your face on the Day of Resurrection. Begging is only appropriate for one who is extremely poor or who is in severe debt, or one who must pay painful blood money.” (Ibn Majah)

There are a number of interesting conclusions we can derive from this hadith.

First, the Prophet was very happy to start a bidding war between competing buyers – indeed he asked a few times in the manner of an experienced auctioneer who knows how to market his products.

We learn from this that negotiating and competing with others in a context where someone will lose out – is fine. This is just business.

Second, there is another hadith: Ibn ‘Umar (Allah be pleased with them) reported Allah’s Messenger ﷺ as having said this: One amongst you should not enter into a transaction when another is bargaining. (Muslim)

The hadith of Ibn Majah seems to go against this, however in reality what happened in this hadith of Ibn Majah is different for two reasons. The first is that the context of the trade is different – this is an auction not a private negotiation. Second, the Prophet, by asking for a higher price was effectively rejecting the offer of the first Companion, and therefore, at the time of the second offer coming in for two dirhams, there was no live negotiation in progress.

Third, for individuals working in the charity sector, this is a powerful hadith about focusing on impact when doing charity and thinking beyond just money. The Prophet could have just donated to the man but instead he donated his social and intellectual capital to come up with a solution that fixed the man up for life.

But while we learn that the Prophet did like to drive a bargain in this hadith, we also know he advised against being too aggressive:

The Compassionate One has mercy on those who are merciful. If you show mercy to those who are on the earth, He Who is in the heaven will show mercy to you. (Sunan Abi Dawood)

He also said:

May Allah’s mercy be on him who is lenient in his buying, selling, and in demanding back his money. (Bukhari)

The Ansar heard that some war booty had come in and presented themselves to the Prophet after Fajr.

On seeing the Ansar, Allah’s Messenger smiled and said, “I think you have heard that Abu ‘Ubaida has brought something?” They replied, “Indeed, it is so, O Allah’s Apostle!” He said, “Be happy, and hope for what will please you. By Allah, I am not afraid that you will be poor, but I fear that worldly wealth will be bestowed upon you as it was bestowed upon those who lived before you. So you will compete amongst yourselves for it, as they competed for it and it will destroy you as it did them.” (Bukhari)

In this hadith the Prophet warned against the dangers of worldly wealth and how it can destroy a people, however before he gave that warning he still said “be happy, and hope for what will please you”, i.e. “you can and should aspire to the good things in this life, but beware of some of the pitfalls”.

In a similar vein, Allah says in the Qur’an:

Once the prayer is over, disperse throughout the land and seek the bounty of Allah. And remember Allah often so you may be successful. (62:10)

The prayer comes first, but then seeking wealth is the next sacred act you should engage in.

There are some basics that we mustn’t engage in as entrepreneurs. We’d like to think they’re pretty obvious so will gloss over these quickly.

The Prophet said:

Whoever deceives/tricks is not from us (Muslim)

Similarly, when we “weigh” something (or the modern equivalent) we mustn’t give less weight than we should when we hand over the good to the buyer.

We mustn’t withhold key information from the buyer or hide defects. We must be truthful in our conduct and words.

Competition can make us do strange things, but it must not let us slip on the basics.

The Prophet said:

Allah loves to see one’s task done at the level of itqan (excellence). (Sahih Muslim)

Competition can stimulate huge leaps forward for humanity because the friction of a worthy competitor can accelerate work ethic and mental faculties like no other.

Thus, competition should be embraced as a catalyst for us entrepreneurs doing our best work and living up to the level of itqan that the hadith talks about.

If you strive to improve your service or product relative to a competitor’s with this hadith in mind, suddenly your entire pursuit becomes a sacred act.

As a corollary to this, the best competitors will seek to avoid copying wholesale what others are doing – they will either build upon it and make significantly better or they will choose a different line of attack. All too often the Muslim entrepreneurial community can be guilty of lacking the itqan in ideation and innovation and opting for the lazy route of copying someone else.

So far we have covered how Islam understands competition in a general sense. In this section we also wanted to comment on competition between institutions working in the Islamic economy.

IFG is an Islamic fintech, for example, and there are many other Islamic fintechs out there globally. At a certain level we all compete for the same (a) eyeballs; and (b) investment money.

Similarly, Islamic charities fundamentally are competing for the same (a) eyeballs; and (b) donor money.

What makes this a slightly unique situation relative to other competitive dynamics is that many of these organisations will have brand statements like “helping deliver halal investment to Muslims” or “helping deliver a trusted charitable solution for donors” – and in reality, if a competitor does that job it shouldn’t matter that the donor or investor did not choose your company.

All that should matter is that the mission is achieved.

Using the above diagram, all that matters is that Good 1 was successfully delivered; it matters not through which seller.

While this may be strictly true, we think it misses a few critical steps:

Having said that, competition between institutions in the Islamic economy should be tempered by the following:

Allah says:

Cooperate with one another in goodness and righteousness, and do not cooperate in sin and transgression. And be mindful of Allah. Surely Allah is severe in punishment. (5:2)

Practically this should mean that those in the Islamic finance or Islamic charitable sector (or other Islamic economy sectors) should look out for each other. There should be an atmosphere of collegiality to the interactions.

Wider industry bodies where the different parties collaborate and work to mutually beneficial goals should be encouraged and actively contributed to.

Where your institution does not offer the solution – or even if it does – make the customer aware of the presence of others and speak of them in good words.

The last point brings us nicely to the opposite of this which we should seek to avoid.

Allah says in the Qur’an:

“O you who have believed, avoid much [negative] assumption. Indeed, some assumption is sin. And do not spy or backbite each other. Would one of you like to eat the flesh of his brother when dead? You would detest it. And fear Allah ; indeed, Allah is Accepting of repentance and Merciful.” (49:12)

Backbiting – speaking ill of someone behind their back – is a major sin in Islam.

In a similar vein the Prophet said:

The real bankrupt of my Ummah would be he who would come on the Day of Resurrection with prayer, fasting and charity, (but he will find himself bankrupt on that day as he will have exhausted the good deeds) because he reviled others, brought calumny against others, unlawfully devoured the wealth of others (Muslim)

When competing with others, things can get heated, and companies and charities can start briefing against one another either openly or behind people’s backs.

However, the only thing that is acceptable to say to a customer are objective statements that explain why you consider that your institution’s offering is a superior offering for a particular type of person.

These comments must never get personal, must never cast doubt on the intentions of others, and must remain respectful and focused on what your institution has to offer.

Individuals should tread incredibly carefully if they take a different fiqhi perspective on something in comparison to another institution – as long the other fiqh position also has good scholarly backing.

Matters of fiqh have never been issues over which Muslims should fall out over – and there are times and places where differences should be engaged with head-on – but fiqh should not be decided through marketing and briefings behind people’s backs.

The Prophet said:

Help your brother – be he an oppressor or oppressed (Bukhari)

The way you help your brother when he is the oppressor is by advising him not be so.

Similarly, the Prophet said:

The one who guides towards good is like its doer (Bazaar)

Our view is that friendly competitors should look out for one another in the Islamic economy and give advice and guidance and correct mistakes or missteps wherever possible.

This is difficult to do – because if you see your competitor mis-stepping the natural thing to do is to take advantage of this. But it is from the perfection of one’s character if one can fight this urge and look to help one’s competitors grow.

This article is written first and foremost to ourselves and we find there are many practices we can and should be working on to improve as individuals and as an organisation.

We hope you benefit from it. If you do, please let us know what you think and what other business topics we should cover by dropping us a message via our contact us page or messaging Ibrahim on his Linkedin.

Please also share with others you think will benefit.

03 December 2025 8 min read

26 November 2025 6 min read

13 August 2025 12 min read

Leave a Reply